New title

This is a reprint from Nevada Magazine Summer 2022 Issue

The tale of one of the Wild West’s last stagecoach hold ups.

BY DAVE McCORMICK

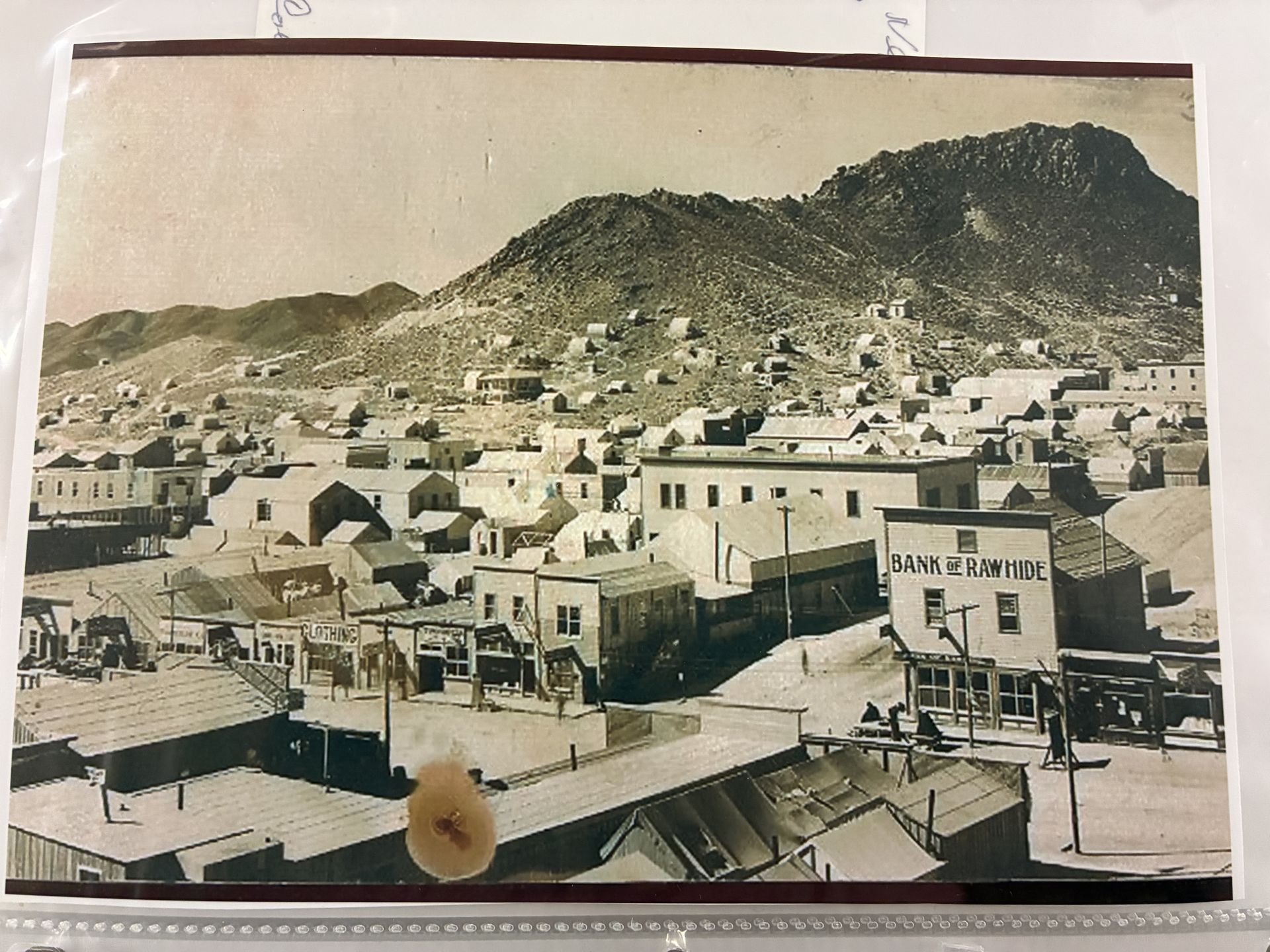

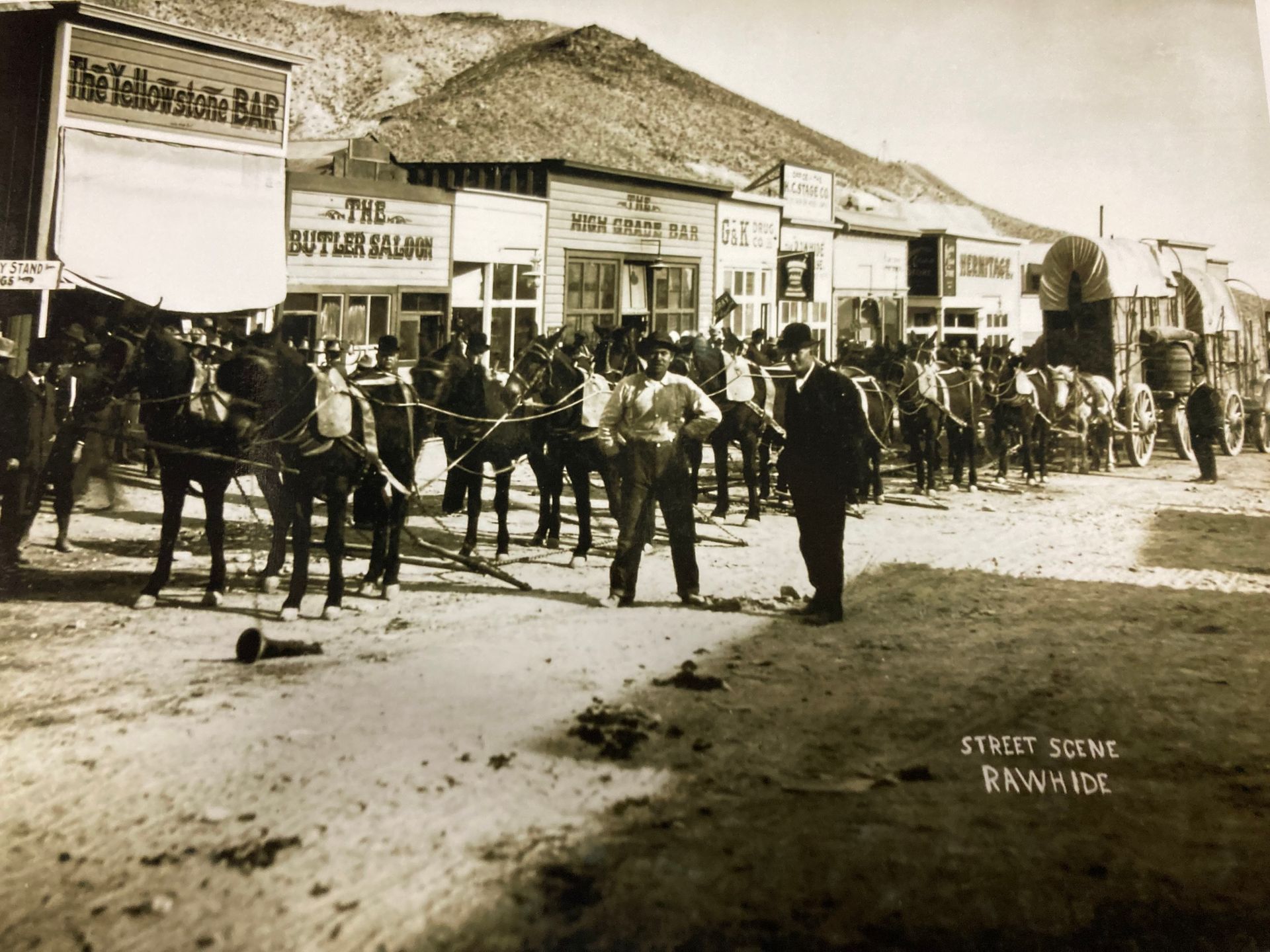

The rough and tumble town of Rawhide—situated about one hour from present-day Fallon—was one of Nevada’s many short-lived mining towns. It was also the location of what is considered the last Wells Fargo strongbox stagecoach robbery.

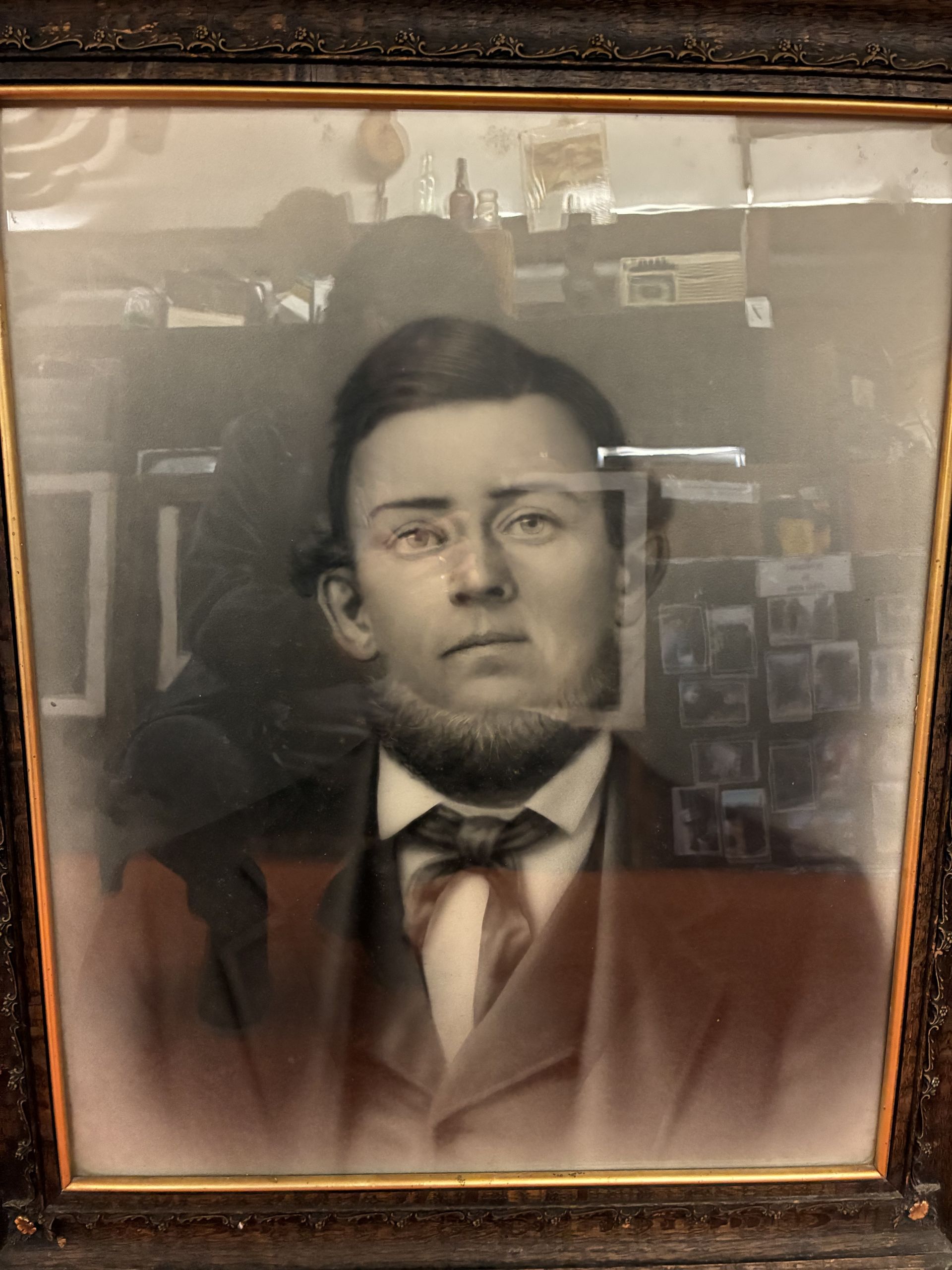

On June 10, 1908, two shady characters entered the stagecoach office in Schurz and bought stagecoach tickets to Rawhide. Three days later, the two men—later identified as C. L. “Gunplay” Maxwell and William M. Walters—rented a small wagon at Pioneer Corral in Rawhide. The two headed back out of town and stopped at the stage line station between Rawhide and Schurz. After grabbing grub from the station, they left their wagon and trekked on foot until they arrived at the top of a knoll with an open view of the stagecoach route. Before long, a stagecoach appeared over the horizon. The would-be robbers came down from their perch and hid behind some boulders near a bend in the road, which caused stagecoaches to slow down.

As the stagecoach rounded the trail, Maxwell and Walters stepped out shouting, “Hands Up!” Walters had tied a bandana over the lower half of his face, while Maxwell wore a burlap bag over his head with eye holes cut out. At the reins of the stagecoach sat Tony Kano, who immediately obliged and pulled the coach to a stop. The stage was carrying mail, two passengers, and—most importantly to the outlaws—a Wells Fargo strongbox. Knowing what the robbers were after, when Kano was asked what was aboard, he simply said, “The Wells Fargo.” “Toss it down,” Walters said.

Kano accommodated and didn’t have to be told twice to “git moving.” The teamster snapped the whip and didn’t slow down until he reached Rawhide. Wells Fargo later reported the take was $1,210. This is considered the last strongbox robbery from the Wells Fargo Stagecoach Company.

The coach operated by Tony Kano was a Concord, the same one that is seen in all the old westerns. Kano sat on the right side and under his seat was a safe called the “the driver’s box” where the Wells Fargo strongbox was kept.

GATHER THE POSSE

As the stage roared into Rawhide surrounded by a cloud of dust, Kano barked that it had been held up. A posse was soon marshaled and dispatched with Captain Cox of the Nevada State Police at the lead. Some posse members were on horseback, others in roadsters and touring cars: an uncanny sight at a wild west stagecoach robbery. The day following the heist, a member of the posse named Sgt. Hunter arrived at the halfway station and spoke to the station manager. Hunter learned about the men driving a small wagon who had come to the station the morning of the holdup. The two had bought rations and feed for their horses, but because they claimed to be broke, the manager sold them the goods on credit. The men said they’d be prospecting nearby, so they left their wagon station and set out on foot. While Sgt. Hunter was at the station, Maxwell suddenly showed up. Maxwell appeared tense, and when he met Sgt. Hunter, he’d identified himself as Thomas Bliss, a deputy sheriff from Goldfield. Maxwell—pretending to be Bliss—told Hunter the prospecting story, though it must have seemed odd when the man who had been penniless the day before laid a 10-dollar gold piece on the counter to settle up his account. Sgt. Hunter sensed something was off and asked Maxwell to ride to Rawhide with him. With the information gathered from the Schurz stagecoach office and Stubler’s halfway station, Captain Cox ordered the men be arrested for the stagecoach holdup. Maxwell was detained while in Sg.t Hunter’s custody, and Walters was quickly located in Rawhide. The next morning, the pair was locked up in the Rawhide jail.

THE TRIAL

The evidence collected might not have been strong enough for a conviction, but after state police explored the robbery scene, they noticed several distinctive boot impressions. Walters’ boots were brought from the Rawhide jail, and Maxwell’s were salvaged from the Simonds store where he had just purchased a new pair. The sole leather on Walters’ boots was worn to shreds, leaving the nails exposed. This matched the nail-riddled footprints at the scene. Maxwell’s boot also had a unique characteristic: a V-shaped cutout on the heel. These prints were also found at the scene. With this evidence, Justice of the Peace H.F. Brede ordered them held for a grand jury. Bail was set at $1,500 apiece, and the two were confined to the Goldfield jail. On August 1, Walters attempted a jailbreak along with other cellmates. Maxwell was not part of the escape and later became a witness for the prosecution. At the grand jury, witness testimony linked Maxwell and Walters to the stage holdup. Ernest Eagon, a teenage passenger of the coach, positively identified Walters, claiming he had the same eyes as the bandana-wearing bandit. The Nevada State police also presented its evidence.

On Sept. 5, 1908, the Esmeralda County grand jury indicted Maxwell and Walters for the crime of robbery. With bail set at $5,000 apiece, it appeared the two robbers would remain in their cells until trial.

JUSTICE IN THE OLD WEST

Odd circumstances surround Maxwell. After the grand jury, his bail was posted anonymously, and the donor is still a mystery. In 1907, under the alias of Thomas Bliss, Maxwell he had actually served in Goldfield in the role of deputy sheriff and, during a murder trial that year, gave false testimony that benefitted an area mining company. Was the bail payment in September 1908 a sort of thank you from the mining company? The answer to that is lost to time. Regardless, Maxwell left the area and was never tried for the Rawhide Stage robbery. Walters, however, was convicted for the attempted jail break and served four years. Shortly before Walters was released, Captain J. P. Donnelley of the Nevada State Police wrote numerous letters to the district attorneys of Esmerelda and Mineral Counties, imploring them to bring Walters to trial for his part in the Rawhide stagecoach holdup.

Donnelley’s pleadings were for naught, and Walters became a free man that same year. Why Walters was never put on trial is unknown.

Maxwell would have been safer behind bars. In 1909 he was involved in an altercation in Price, Utah, that soon involved Deputy Sheriff Edward Black Johnson. Johnson and Maxwell had known each other previously and held no hospitality towards each other. On August 23, Johnson confronted Maxwell in the middle of the street. The heated words between the two men evolved into gunfire. Maxwell was shot dead.

New paragraph